The past few weeks in the world of space have been pretty hectic. Most especially because of the fantastic new views of Pluto we've been receiving, courtesy of the New Horizons flyby (which I wrote about in my last postcard). We've also been hearing about the "frozen primordial soup" of organic compounds detected by the European Space Agency's Philae lander on comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, as detailed in a new special issue of Science. Some of these compounds may be important for the prebiotic synthesis of amino acids, sugars, and nucleobases, i.e., the very ingredients of life.

|

| The surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, as imaged from 9 metres away. Credit: ESA |

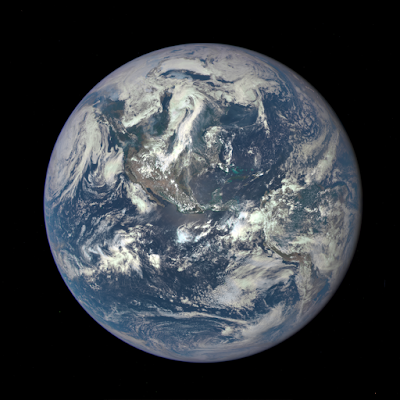

But there are two other recent news items I want to focus on in this postcard. First, the new photograph of the Earth captured by NASA's new Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite. And second, the recent discovery of an exoplanet that is being billed as Earth's 'twin'.

On 6 July 2015, the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) instrument on DSCOVR returned its first view of the entire sunlit Earth. Safe in its gravitationally stable location one million miles away—at a so-called Lagrange point—the satellite was able to obtain this kind of full-Earth portrait for the first time since the famous 'Blue marble' photograph was snapped by the Apollo 17 astronauts whilst on their way to the Moon in 1972. I've mentioned that older, stunning photo in a previous postcard, but as the most reproduced image in history, I think that it is more than worth showing again.

|

| The famous and historic 'Blue marble', taken during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. Credit: NASA |

It might come as a surprise that it has taken more than 40 years to recapture Earth in a similar view. The pictures you've seen of Earth's full disc in the meantime have either been this Apollo 17 photograph, or composite images (i.e., several smaller images that have been stitched together). It is difficult to obtain these images because many variables come into play. The camera must be between the Earth and the Sun, and far enough away to capture the whole planet in its field of view. Although weather satellites—in geosynchronous orbits—get similar views, they cannot normally see an entire hemisphere without shadow.

|

| The Earth, from one million miles, as seen by the Deep Space Climate Observatory on 6 July 2015. Credit: NASA |

The data from EPIC will primarily be used to measure changes to the ozone and aerosol levels in Earth's atmosphere, as well as cloud height, vegetation properties, and ultraviolet reflectivity characteristics. But these new, beautiful, images of a whole Earth remind us how powerful it is to see our entire home in one go. As pointed out by John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, "these new views of Earth give us an important perspective of the true global nature of our spaceship Earth."

Indeed, I'm reminded of an excellent book I read several years ago by Robert Poole. In Earthrise: How Man First Saw The Earth, Poole tells the story of how images of Earth—such as the Blue marble and the equally famous Apollo 'Earthrise'—taken during the dawn of the space age, played a huge role in the birth of the now-popular environmental and conservation movements.

It is another aspect of these images of our blue Earth, however, that strikes me most. It is the human capacity for intelligence and creativity that enables space exploration and capturing of Earth-selfies from afar. Yet we do not see evidence of our presence in these pictures. In many ways, we are invisible to the universe. It is not life that makes Earth special. It is the blue oceans, the green forests, and the white wispy clouds in our lovely oxygen-rich atmosphere that make our world habitable. So for this postcard to our hypothetical alien planetary geologists, I want to send a snapshot of our whole world. Let them see the Earth and all its systems intertwined.

The uniqueness of Earth, however, might be under threat if a new discovery from the Kepler space telescope is anything to go by. On 23 July 2014, scientists working on the Kepler mission announced that they have found the most Earth-like extrasolar planet yet. The new planet—known as Kepler-452b—is located about 1,400 light years away, and is a similar size to Earth. In addition, Kepler-452b orbits a Sun-like star at a distance that is similar to that of Earth around the Sun. The planet is being hailed as "the first possibly rocky, habitable planet around a solar-type star". And it will thus, likely, become the focus of an intense search for extraterrestrial life. Perhaps we'll even find those alien planetary geologists there waiting for us.

At a time when humanity seems to be as fractured as ever, perhaps we need a wake-up call like these ones from NASA. We need to be reminded every once in a while that we are all one family, stuck together here on our little spaceship Earth. We should do our utmost to look after it—and each other.

|

| 'Earthrise' photograph taken by astronaut Bill Anders during the Apollo 8 mission, on 24 December 1968. Credit: NASA |

It is another aspect of these images of our blue Earth, however, that strikes me most. It is the human capacity for intelligence and creativity that enables space exploration and capturing of Earth-selfies from afar. Yet we do not see evidence of our presence in these pictures. In many ways, we are invisible to the universe. It is not life that makes Earth special. It is the blue oceans, the green forests, and the white wispy clouds in our lovely oxygen-rich atmosphere that make our world habitable. So for this postcard to our hypothetical alien planetary geologists, I want to send a snapshot of our whole world. Let them see the Earth and all its systems intertwined.

The uniqueness of Earth, however, might be under threat if a new discovery from the Kepler space telescope is anything to go by. On 23 July 2014, scientists working on the Kepler mission announced that they have found the most Earth-like extrasolar planet yet. The new planet—known as Kepler-452b—is located about 1,400 light years away, and is a similar size to Earth. In addition, Kepler-452b orbits a Sun-like star at a distance that is similar to that of Earth around the Sun. The planet is being hailed as "the first possibly rocky, habitable planet around a solar-type star". And it will thus, likely, become the focus of an intense search for extraterrestrial life. Perhaps we'll even find those alien planetary geologists there waiting for us.

|

| Artist's concept of Kepler-452b in orbit around its parent star. Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T.Pyle |

No comments:

Post a Comment